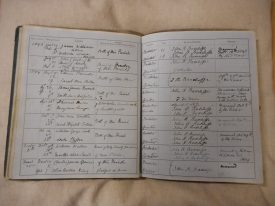

Registers of Banns of Marriage

The baptism, marriage and burial records found in parish collections held at Warwickshire County Record Office are the family historian’s bread and butter. Banns registers, however, are an often overlooked resource. These registers record the banns (or intent to marry) for intended couples being read out for what was (and still is) usually three consecutive weeks prior to the marriage taking place.

Most people had marriage by banns as opposed to the more expensive option of a licence (hence the comment made by Mrs Bennett in Pride and Prejudice when she says to her daughter, ‘And a special licence. You must and shall be married by a special licence’).1 Whether a couple were married by banns or a licence was usually recorded in the marriage register when the pair got married and so may be an indication of their social status – or indeed how quickly (or public) they wanted their marriage to be.2

Many a slip…

Sometimes, however, history is just as much about what did not happen than what did. Whilst a licence would not guarantee that the marriage would (or could) go ahead3 , the reading of the banns gave three opportunities prior to the date of marriage of anyone raising objections to the marriage.

Though the majority of marriages went ahead, you occasionally find entries in the banns registers where this was not the case. For example, Thomas James Russell (widower) and Edith Lucy Ashfield (spinster) had banns read out at Snitterfield parish church for three consecutive Sundays at the end of August and beginning of September 1894. However, the marriage never took place as the vicar noted that ‘the woman supposed to be married, ran away with money & the Wedding Cake’.4

Transportation and bigamy

During the nineteenth century, one common form of criminal punishment was ‘transportation beyond the seas’ to colonial settlements on the other side of the world in Australia and Tasmania. Though this was meant to be for a limited time period, many convicts ended up settling there either by preference or from limited means of getting back home. Letters too may have been a problem, whether out of illiteracy, funds or even disinclination. It would furthermore have been many months before any news could be conveyed back home.

So, if a wife (or husband) was left alone, at home, it would be quite conceivable for them to hear nothing from their spouse for many years and desire to marry again. The common law rule in 19th century England was that if a spouse was absent and unheard of for seven years, they could be presumed dead – a defence in a charge of bigamy.5

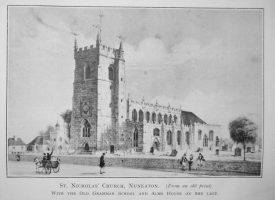

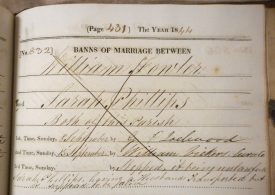

In 1844, the marriage between William Fowler and Sarah Phillips at the parish church of St Nicolas, Nuneaton, was stopped on the third time of asking, as ‘it being unlawful, Sarah Phillips, having a Husband Transported but is supposed to be alive’.6 Unfortunately, a look at the Warwickshire Quarter Session and Assize Calendar of Prisoners database throws up no likely candidates for Sarah’s husband (though perhaps Phillips was her maiden name) so we can’t tell just how long Sarah’s husband had been absent.

So, whilst the banns registers often throw up more questions than answers, they give intriguing glimpses into moments in our ancestors’ lives when things could have turned out very differently.

1 Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice (1813), chapter 59.

2 Licences were usually obtained from the diocese, so for Warwickshire are usually held by either Worcester Archive or Lichfield, now Staffordshire County Record Office.

3 Hence the crucial plot moment in Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre (1847).

4 Register of banns of marriage for the parish of St James The Great, Snitterfield, Warwickshire County Record Office, reference DR 382/1.

5 Henry Alan Finlay, To Have But Not to Hold: A History of Attitudes to Marriage and Divorce in Australia 1858-1975 (2005), p.30-32.

6 Register of banns of marriage for the parish of St Nicolas, Nuneaton, Warwickshire County Record Office, reference DR 280/5.

Comments

Sarah and her first husband Richard Phillips were my gr. gr grandparents. We`ve done some research in the family, and know that Richard was convicted of receiving stolen goods at Warwick Assizes in 1840. Warwick Advertiser Sat. 4th April 1840. He was transported to Tasmania for 10 years and remarried another convict in 1850 and went on to be a gold miner in Victoria. Sarah left alone with two children had her marriage banns to William Fowler rejected in 1844, but married him in 1848 and had five more children. She died in 1855 aged 38.

Add a comment about this page