For 33 years the extensive coalfield of Warwickshire had been free from serious disaster. Tragically this impressive record was marred by a calamity that took place at the Exhall Colliery in the early hours of 21st September 1915.

A paraffin lamp was overturned, causing the headgear of the down shaft to catch fire. The lives of all 375 men in the workings of the pit that night were put at risk. Fumes and smoke quickly filled the tunnels and sadly fourteen men suffocated. However one man’s prompt action in closing the separation doors to limit the amount of smoke that entered the workings helped to save the rest of the men.

Stark language

The official statement made by Mr. C. F. Jackson, Manager of the Colliery, tells the story of the disaster in stark language:

“The fire occurred at this colliery in the early hours of this morning, the gear of the downshaft being in flames. There are haulage wheels near the pit top and it is necessary that these should be oiled during “snap” time. The man entrusted with this work went to oil them this morning, taking with him a paraffin lamp, which was accidently dropped. This set fire to the woodwork at the top of the shaft, and as the ventilation fan is situated half a mile away the fire got a fairly good hold and damaged the timber about 20 yards down the shaft. The discovery was made at 2.20am and by 4.20am the fire was out and the men were being rescued up the upcast shaft at Black Bank. Three hundred and seventy-five men were in the workings and all these were safely recovered with the exception of fourteen who were found at the foot of the hill and whose dead bodies are now being brought up.

On my arrival at the pit-head fifteen minutes after the outbreak,” said Mr. Jackson, “I at once ordered the ventilation fan to be stopped. The men underground have had instructions as to what steps to take in case of fire, and the foreman in charge, remembering those instructions, at once closed the separation doors, short circuiting the air and preventing smoke in any volume getting into the workings. It was due to this prompt action that we have been able to rescue the great number. As soon as the fire was extinguished the working of the fan was resumed, and this at once made the underground conditions practically normal.

Rescue parties at once descended; simply walking into the workings and finding the men who had been suffocated. The men who met their death must have taken a different way to their comrades, walked into the fumes, and been immediately overcome. Their end was very peaceful, and not a single dead man has received any actual injury to the body.

The company’s fire fighters tackled the outbreak but so great was the heat that the bond on which is suspended one of the cages snapped, while another hauling rope bring coal tubs from the face to the foot of the shaft was also severed, causing a train to run away and be smashed to pieces. Use was made of an emergency shaft, half a mile away at Black Bank, and this entailed some of the miners walking a distance of two miles underground to safety. The majority of the men were quickly brought to safety, though nineteen were missing, fourteen afterwards being found dead, and five overcome by the fumes. It was not till well after mid-day that the cage ascended with victims of the disaster.

At two o’clock preparations were being made to bring the dead bodies to the surface.”

A solemn and lengthy task

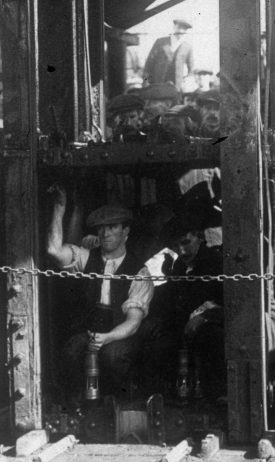

This was the beginning of a solemn and lengthy task, with body after body taken from the cage at intervals of about 20 minutes and carried to the improvised mortuary a few yards away. The sight of the sad burdens, roughly wrapped in felt and carried gently by their cold, begrimed fellow miners, brought tears to the eyes of even the strongest men.

In the midst of this dreadful undertaking came an unexpected blessing. Beneath three dead miners, a young lad, Bert Pearson, was discovered alive. The weight of his fellow miners collapsing had caused Bert to fall and lose consciousness. However this saved his life, since he was prevented from breathing in the deadly fumes. As the air in the tunnels improved Bert woke to find he was trapped. Rescuers recovering a body heard him call out and rushed him to safety.

The inquest into the disaster is covered in this article.

The memorial in St. Giles’ Meadow, Exhall, to the miners who perished, will be unveiled by the High Sherriff of Warwickshire, Janet Bell-Smith, on 20th September 2015.

Comments

Add a comment about this page