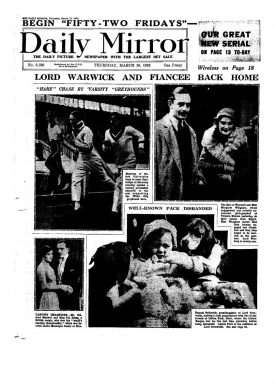

There was a cold breeze sweeping by as they stepped off the train. The slight patter of rain dripped onto the eagerly anticipating journalists who had been waiting all morning for their arrival. As they moved through the station towards the exit, crowds of well-wishers poured forward as those scribbling notes clambered to get the best view. She, looking bewildered yet conveniently dressed, laughed out ‘how did our secret leak out?’ A couple of flashes partly caught the gaze of them. She was handed a large basket of azaleas by a friend as he stood by awkwardly smiling into the distance.

The place was Victoria Station, London. The date was Wednesday 9th March 1932. She was Margaret Whigham and he was Charles Fulke Greville, seventh Earl of Warwick. The young, bashful earl – who had only six months ago been nominated as one of the 15 most eligible bachelors in the British Empire – had returned from his service with the Grenadier Guards in Egypt where he had met, for the very first time, the beautiful and popular debutante Margaret Whigham.

Within three weeks the pair were engaged. Margaret, despite having already promised herself to another man, could not resist the soft-spoken, hopelessly romantic, oft-clumsy, and glamorously titled young earl. For the hapless earl, the engagement to the starlet of Society, had washed away the coldest and decadent memories of his childhood. For one of the first times in his life, the young Lord Warwick had a genuine smile on his face.

Celebrity and sensation

For all the celebration and sensation orchestrated in the press, the ‘couple of 1932’ did not enjoy the healthy ingredients for matrimony. Buried deep within the Warwickshire County Record Office, stuffed in between political papers and bills are the private correspondence between fiancé and fiancée revealing the truth behind one of High Society’s greatest dramas of the early 30s.

Warwick was in love, there could be no doubt of that. In a letter written to Whigham, he joyfully expressed ‘the whole of Warwickshire has gone mad’ with excitement for the prospect of a future countess of Warwick. Whigham recorded in her memoirs however, that on arriving at the castle, her future home, she felt nothing but disdain and coldness from her future husband as he spent most of the day sleeping while his mother gave her a guided tour. Whigham retreated to her home estate and wrote a letter back to Warwick saying:

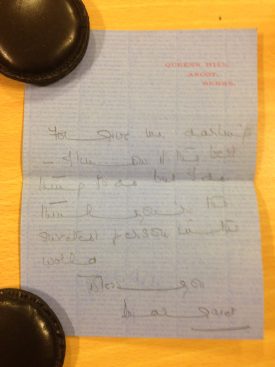

My sweet I would rather wait another week or two before I talk to you again. Of course I love you and think I still do but whether we’re going to be happy together is quite another thing and that’s what I want to try and decide before I see you.

Warwick, not willing to be shunned, flooded her with flowers, chocolates, and romantic poems. He pushed forward with the wedding arrangements and prepared for his wife to move into the castle. And, as if to reinforce – and partially convince himself – that the wedding would take place, the the Daily Mail and Daily Mirror recorded the preparations every step of the way. Had this been the late 19th century, the wedding would have been considered one of glamorous extravagance; a mark of the aristocracy’s unbroken pomp and power.

Not of the aristocracy

But Whigham was not of the aristocracy and marriage was no longer the prerequisite of a woman’s existence. The 20s had been marked by a new stream of plutocrats, actors, merchants, musicians, and any young man or woman with money that had irreversibly changed the fabric of High Society. The blue-blooded men with ancient names still commanded the most celebrity, but Society was no longer played by their rules.

Four weeks after their return home, Warwick and Whigham’s engagement was ended. In an undated letter, but no doubt immediate, Whigham wrote ‘forgive me darling – I know it’s the best thing to do but you are the sweetest person in the world.’

All quotes are from Warwickshire County Record Office reference CR1886/645 – Personal and Official Papers, 20th Century (Grevilles of Warwick Castle). The letters are unorganised and uncatalogued within this box.

Comments

Add a comment about this page