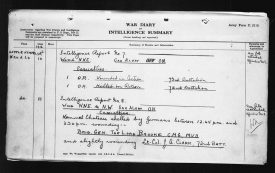

A strong wind was blowing across the trenches. A putrid smell lingered in the air, a mixture of chlorine gas, mud, filth, and flesh. It was approaching lunchtime in the town of Little Kemmel after a quiet, unassuming morning. The war had been pretty timid after military command turned attention towards the bloody battlefields of the Somme. The commanders had prepared lunch and began dining, laughing, and singing around 12.30pm. Within 20 minutes, the chateau they had converted into their Ritz-like retreat was shelled to the ground. It was 11th September 1916.

The most important casualty was Brigadier-General Lord Brooke, otherwise Leopold Guy Greville, eldest son of the 5th Earl of Warwick. He had taken shrapnel into the hand and thigh and was evacuated to London. It was symbolic of the trivial military career that the infamous ‘military adventurer’ Lord Brooke had become, and who would be the last (future) earl of Warwick to fight on the battlefield. He had been drafted into the Canadian Army by his close associate, notorious Minister of Militia Samuel Hughes, and risen the ranks from Training Officer to Brigadier-General in a matter of months, despite protestations from other senior army officials that Lord Brooke lacked military competence.

Disastrous military endeavour in Ypres

He led a disastrous military endeavour in Ypres, 1915, and only through his close contacts, and occasional dinner parties at White’s gentleman’s club did he retain his position. He took command of the 12th Canadian Infantry Brigade in July 1916, and embarked for France in August 1916. Living up to the role of aristocratic warrior-leader, he was leading his troops towards Somme but his journey was cut short just one month later in Ypres – the site of his first dismal campaign scarcely a year previous.

It has been quite well-documented that Lord Brooke succumbed to death at an early age (45 years old) in 1928 and it has often been associated with the horrors of the frontline, suffering from shellshock, turning to alcohol for relief, and ending his dismal experience in a Brighton nursing home in 1928. Letters stocked in the Warwickshire County Record Office certainly do support the notion of a traumatic decade for the Warwick family throughout the 1920s.

Fled the town

His wife, Elfrida, had fled the town abroad with her two sons in 1925. The marriage had broken down in a saga befitting a midweek soap opera. Having recurring pain from his war wounds Leopold acquired a nurse, Miss Baldwin, to support him. Taking his nurse as his lover, Leopold moved out of the castle into the Malt House in Mill Street. As his wife confronted him he lashed out violently, forcing her to flee, and she refused to return as he was ‘still too violent and at times too unwell.’

Lord Warwick’s condition worsened. On one occasion, ‘when going to have his bath, he unfortunately fell against the side, knocked the soap dish down, and this breaking, he fell upon it. He bled very furiously for a time, but the Doctor was able to stitch up the wound and everything is going on well, but I’m afraid it is very uncomfortable for him.’

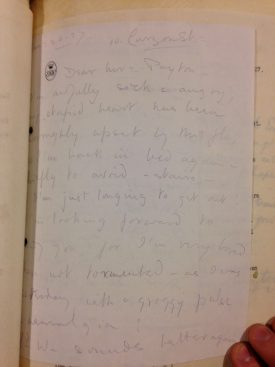

The effect was devastating for the Countess, who saw no more ‘better times with Lord W, I can only see them without him.’ Speaking bluntly, the countess sent a letter to Warwick’s agent, Mr Godfrey-Payton: ‘he is never likely to meet us again unless he has a stroke – which HEAVEN DEFEND HIM FROM – that he may do something that will hurt them.’

Not of sound mind

But Warwick was clearly not of sound mind. In a letter written by Godfrey-Payton to the Countess, he saw that ‘it’s a pretty state of affairs if Lord W is left alone locked in to his house! I expect he is ill and probably very frightened and required some affectionate care, and I wish with all my heart it were possible for you to be with him.’

Leopold succumb to death in a nursing home in 1928, finally reconciled with his wife and children on his deathbed. The true nature of his illness and death have been lost to time – the records of the nursing home in Brighton went up in flames during the Blitz – but whether it was through the horrors of the war, a hereditary disease that struck down the previous four earls of Warwick, or losing the sheer will to live through pain and suffering, the Roaring Twenties were as close as the Warwick’s came to apocalyptic sadness; it was a disaster that the family would never quite recover from.

All records of the Earl of Warwick on the Frontline are from recently released documents in the Canadian National Archives

All records of letters exchanged in the 1920s are from the WCRO CR1886/894/2

Comments

Add a comment about this page