This month marks the 100th anniversary of the Military Conscription Act – which required all single men between the ages of 18 and 41 to sign up for military service in the First World War.

All men had the right to appeal their conscription and The Great War: National Service Appeals Tribunal files held in the Warwickshire County Record Office collection provide information about the individuals who appealed and reveal fascinating details about personal and family circumstances, and the reasons given for seeking exemption.

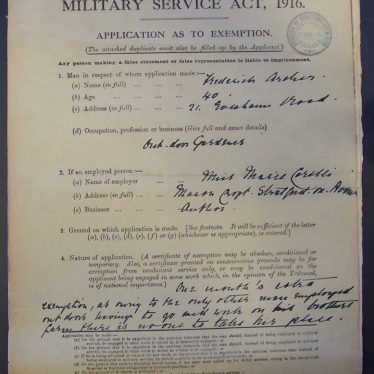

In one file from the collection1, famous Stratford author Marie Corelli requested a temporary exemption for her gardener Frederick Archer as she believed her garden and the parts of her house maintained by Frederick would suffer in his absence.

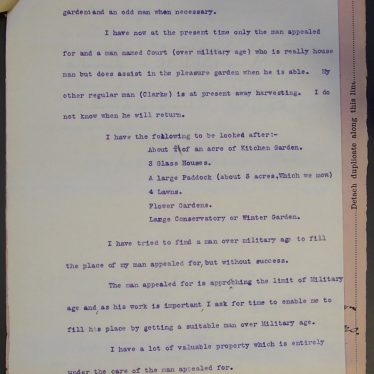

Frederick was 40 years old at the time of his conscription, almost too old for service anyway (the age limit was extended later in the war). Mrs Corelli asked for a delay to Frederick’s conscription to give her time to employ a replacement. As she reported to the tribunal in a supporting letter, it was difficult to find a suitable man over military age.

Unfortunately, the appeal was refused and Frederick would have been forced to sign up to military service. The Tribunal papers do not give details of where he was sent to serve, but given his age, he is not likely to have been sent to the Front Line. He may well have been required to undertake essential war work on the Home Front, such as munitions work, farming or shipbuilding.

We do know that Frederick survived the war. He died in 1932 and is buried in Stratford Municipal Cemetery alongside his wife, Lucy.

Appeals Tribunals

Until March 1916 enlistment had been voluntary and many people are familiar with Lord Kitchener’s famous campaign ‘Your Country Needs You’, but voluntary enlistments proved insufficient as the war continued and casualties increased. The Military Service Act 1916 allowed Britain to use conscription for the first time and put Britain on a ‘total war footing’.

Initially, the act conscripted all single men aged 18-41 and an amendment a few months later extended the conscription to all married men. Later in the war as manpower continued to decrease, the upper age limit was extended until in 1918 it was set at 51.

Every man had the right to ask for an exemption and Tribunals, which had already been set up during the voluntary enlistment period, were now continued on the statutory basis at local, county and central level. There were 2,086 local tribunals and three months after the Military Service Act came into force, 748,587 men had appealed.

Exemptions

Most men were given some kind of exemption, usually temporary, to allow for arrangements to be made at home or by employers. Small businesses often suffered greatly with the loss of employees and occasionally, in cases where extreme domestic hardship would result, men were granted exemptions.

One of these cases is contained in the Middlesex Tribunals records held by the National Archive. John Shallis appealed on the grounds of domestic hardship, having lost four of his brothers during the war.

On his appeal form he explained that his mother had broken her leg, and his father was away carrying out Home Defence duties with the Territorial Force. However, it was likely his work in munitions tipped the balance with the local Tribunal and he was granted exemption.

Marie Corelli

Marie Corelli was one of the Victorian age’s bestselling novelists, selling more books than contemporaries Rudyard Kipling, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and H G Wells combined. Born the illegitimate daughter of Charles Mackay, a journalist and songwriter, she was a talented pianist and adopted the name of Marie Corelli for a short-lived stage career.

Fortunately, she also discovered a talent for writing popular novels, and quickly. Her first, A Romance of Two Worlds, was published in 1886 and found a surprise fan in Oscar Wilde. The novel combined mysticism and pseudo-religion, appealing to the contemporary interest in the occult.

Popular success followed

Further popular success followed, although her novels never attracted critical acclaim, and she moved from London to Stratford in 1899.

She lived in Mason’s Croft, a former townhouse and educational establishment which she fondly imagined to have associations with Shakespeare. The Watchtower that she believed to be Elizabethan was in fact a Victorian folly.

Mason’s Croft did not fall into disrepair after Frederick left, and is now the home of the Shakespeare Institute of the University of Birmingham.

References

James McDermott, British Military Service Tribunals, 1916-1918 (Manchester, Manchester University Press: 2011).

http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/conscription-appeals/

https://everydaylivesinwar.herts.ac.uk/

William Stuart Scott, Marie Corelli – The Story of a Friendship (London, Hutchinson, 1955) Available in the WCRO Reference Library C 920 COR

Thomas FG Coates and RS Warren Bell, Marie Corelli – The Writer and the Woman (London, Hutchinson, 1903) Available in the WCRO Reference Library C 920 COR

1 Warwickshire County Record Office reference CR1520/Box 59/Meeting 20

This article is March’s Document of the Month for the Warwickshire County Record Office. Further articles can be found on their website.

Comments

What a fascinating insight into conscription and Miss Correlli. Love the work you do!

Add a comment about this page