Today, Rupert Brooke is possibly best known as a War Poet and is included on the Poets of the First World War memorial in Poets’ Corner, Westminster Abbey, alongside fellow poets, Wilfred Owen, Edmund Blunden, and Siegfried Sassoon. There is more to Brooke than this however, and his war poems only account for a small proportion of his work.

Of course Brooke’s early life was rooted in Warwickshire. He was born on 3rd August 1887 at 5 Hillmorton Road in Rugby, Warwickshire, to William Parker Brooke (1850-1910) and his wife, Ruth Mary Brooke (née Cotterill), the second of three sons. His father was classics tutor and later housemaster of School Field at Rugby School, which Rupert himself attended after studying as a day boy at Hillbrow preparatory school.

Early poetic promise in Rugby

At Rugby, he won a prize in 1905 for his poem, ‘The Bastille’, and excelled at sport. Brooke went on to read Classics at King’s College, Cambridge between 1906 and 1909. During this period, Brooke embraced various Cambridge groups, including the Apostles (an exclusive discussion group) and the Fabian Society. He also became one of what his friend Virginia Woolf would later call the ‘neo-pagans’, embracing outdoor exercise, vegetarianism, and alternative lifestyles, and having a strong interest in socialism.

A return to Rugby

His time in Rugby was not over, however. After he completed his degree, he lived in nearby Grantchester continuing his academic studies and writing. His father died in January 1910 and Rupert went back to Rugby to cover as Deputy Housemaster for a term. Shortly afterwards, his first volume of poetry, entitled Poems, was published in 1911. The following year, he helped Edward Howard Marsh (then Winston Churchill’s Private Secretary) publish the first of his Georgian Poetry series.1 Brooke contributed several poems to Georgian Poetry 1911-1912, including one of his most famous poems, ‘The Old Vicarage, Grantchester’, which he had written while away in Berlin.

During 1912, however, Brooke had a nervous breakdown, part precipitated by his complex web of chaste and sexual relationships, and (potentially) confusion over his own sexuality.2 Early in 1913, Brooke wrote ‘Youth’s Funeral’3 whilst staying with his friends, Francis and Frances Cornford, in Cornwall. Later in the year he earned his longed for Fellowship at King’s College and then travelled abroad in order to restore his health, visiting the United States, Canada, and the South Sea Islands. A collection of prose essays of his time abroad was published posthumously as Letters from America in 1916 with an introduction by Henry James.

War poetry and death

Rupert returned to England in June 1914 and, soon after war broke out in August, enlisted in the Royal Navy. Though he was at the siege of Antwerp, he saw little action. Shortly after this, he wrote his famous war sonnets, including ‘The Soldier’, which were published in New Numbers in December 1914. Having joined the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force in February 1915, Brooke sailed for Gallipoli, but he died at sea on 23rd April after contracting septicaemia from a mosquito bite. Winston Churchill paid tribute to him in The Times and Lascelles Abercrombie’s obituary in the Morning Post (27 April 1915) quoted from Brooke’s ‘The Funeral of Youth’.4 Later that year, Brooke’s 1914 and other Poems (including ‘The Funeral of Youth: Threnody’) was published posthumously; his Collected Poems were edited by Edward Marsh, his literary executor, and published with a memoir in 1918.

Legacy

Whilst Brooke is commemorated as a war casualty, the circumstances of his death meant he was buried in an isolated grave on the island on Skyros. His friend and fellow solider Denis Browne described Brooke’s burial place as ‘one of the loveliest places on this earth, with grey-green olives round him, one weeping above his head’.5

In his introduction to Letters from America, Henry James described Brooke as ‘young, happy, radiant, extraordinarily endowed and irresistibly attaching’. Along with the patriotism of his 1914 sonnets, the image of an innocent young poet tragically killed in the course of war prevailed for many years, an image which was carefully maintained by his friends and literary trustees. In reality, Brooke was a more complex character.

References

1 See Great Writers Inspire podcast (University of Oxford), ‘Georgians and Others’ by Dr Stuart Lee.

2 By this time, Brooke had been romantically involved with Noel Olivier, Katherine (‘Ka’) Laird Cox, Phyllis Gardner and the actress Cathleen Nesbitt. An oral history interview of Cathleen Nesbitt, which touches on her relationship with Rupert Brooke, is available on the Imperial War Museum website.

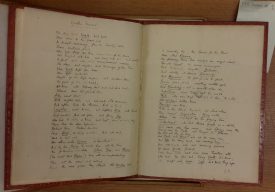

3 A fair copy manuscript of Rupert Brooke’s poem ‘Youth’s Funeral’, published as ‘The Funeral of Youth: Threnody’ (shelfmark MS. Don. d. 1) is held at the Bodleian Library. In the published version, the poem is described as a threnody, a memorial lament, and is an epitaph for bygone days of youthful innocence.

4 Quoted in ‘Rupert Brooke (3 August 1887-23 April 1915)’ in Patrick Quinn (ed.), British Poets of The Great War: Brooke, Rosenberg, Thomas: A Documentary Volume, Dictionary of Literary Biography vol. 216, Gale, 2000, p. 5-97.

5 Rupert Brooke and Edward Howard Marsh, The Collected Poems of Rupert Brooke : With a Memoir (1918).

This is an edited version of the post ‘Youth’s Funeral’ by Rupert Brooke, originally posted on the Bodleian Library’s blog, and is reproduced with their permission.

Comments

Add a comment about this page