There are many black days in British economic history, but before Black Wednesday and Black Monday there was a Black Tuesday, 6th September 1887, when the Bank of Greenway, Smith and Greenways was forced to close its doors owing £275,000 to its creditors, the equivalent of £22 million today.1

Everyone from the Lord Lieutenant and the Warwick Corporation, to widows with a small annuity, had invested in the bank – an institution run by well-known and respected members of the community and operating for almost 100 years. It had become a vital part of the county economy.

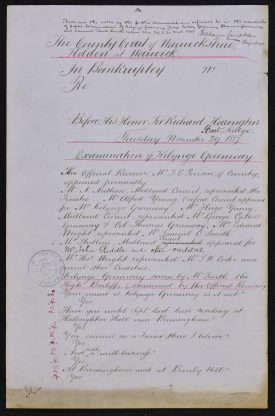

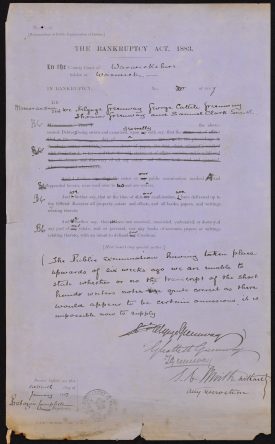

This document2 features some of the 428 pages of testimony given by the bank’s owners, Kelynge, George (Warwick’s Town Clerk) and Thomas Greenway and Samuel Smith (the County Treasurer) a few weeks after the crash.

A brief history of the bank

The bank was founded in 1791 and Kelynge Greenway joined the management team in 1855 when he was left an interest in the firm by his uncle. Although they had no financial or banking experience, Kelynge brought his brothers on board and by 1862, the operating capital of the bank stood at only £7.3 Smith, although experienced, was a junior partner and not allowed to take part in policy decision-making.

The Greenways’ testimony suggests they not only used their investors’ capital to finance the banking business, but also took vast sums from the bank themselves – often far in excess of any profits made. When Greenway, Smith and Greenways was forced to close, angry investors marched in protest before the bankruptcy hearing, burning the Greenways in effigy and carrying banners showing the amounts they were owed.

‘Callous and supercilious’4

Observers noted that Kelynge Greenway seemed unaffected by his role in the downfall of the bank, whereas his brother George had aged visibly and his hair had whitened by the time of the bankruptcy hearing. Kelynge Greenway became famous for his stock response to difficult questions, ‘I don’t follow you’. This became a catchphrase around Warwick, according to J. Lloyd Evans. He answered even simple questions with baffling obfuscation. When asked to explain a discrepant account, he said, ‘I do not think it is reliable. I think it is only an estimate’, and then admitted it was in his own handwriting. He acknowledged that his brothers each paid in £8,000 when they joined the bank, but this went to Kelynge’s private account and not into bank funds.

When the bank sank with overwhelming debts, they were largely due to continuing investments in two projects which Kelynge Greenway had persisted, but which he acknowledged were unwise. One was the Magdeburg Tramway. With no capital at his bank, Greenway asked for a loan to finish the Magdeburg Tramway in 1886, describing it as ‘helping a lame dog over a stile’. The loan was granted, but to the Greenways as individuals, not the bank. However the Tramway was still listed as a bank asset.

The Bank’s other major investment in the Kenilworth Tannery proved even more controversial. When the business generated a £14,000 overdraft rather than recovering the debt, Kelynge Greenway installed his cousin initially as partner and finally as sole manager of the leather business. Philip Newman, M.A. was a schoolmaster with no tannery experience, but was provided with £25,000 to continue the business. More money was invested by the Greenway family and friends until eventually the Tannery’s overdraft reached £85,000 and the separate account set up was stopped. Representing over 200 of the bank’s creditors at the Bankruptcy hearing Mr Thomas Wright, a solicitor from Leicester, questioned the continued support of Mr Newman’s bad debt, suggesting that the Greenways were using Newman’s name and the Tannery account to cover their own expenditure. Kelynge Greenway replied to this sanguinely, ‘Not that I am aware of; this is the first time I have heard of it.’

Fallout from the crash

The effects of the crash were felt across Warwickshire and beyond. Welfare payments made the day before the bank closed were worthless the day after, and one man travelling from Texas to Kineton to receive an inheritance found that his legacy was lost. Greenway notes in circulation at the time of the crash were worth about £13,000. They were as highly valued as Bank of England notes by local people, and many had stored them for a rainy day. When they were sold after the crash, sellers received two shillings for every pound. Many residents felt the effects as the Warwick General District Rate was increased by threepence in the pound as a result of the crash.

This article is Document of the Month for August 2018 at the Warwickshire County Record Office. Further articles can be found on their website

1 National Archives Currency Converter, http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/currency-converter/#currency-result, accessed 20 July, 2018.

2 Warwickshire County Record Office reference CR556/1

3 Evans, J Lloyd, ‘The History of A Bank Smash’, Warwick, 1888, p.9.

4 Evans, ‘Bank Smash’, p.21

Comments

Add a comment about this page