The mystery of why Nicholas Brome demanded to be buried standing up in the doorway of the church at Baddesley Clinton inspired me to research the life of this 15th century lord of the manor, and eventually to write a novel. Two things intrigued me: why did he feel the need to be buried upright where everyone entering the church would tread on his head, and why had his original grave been replaced with a small marker-stone easily hidden by the doormat?

A tour of the manor house some years ago confirmed that Nicholas had written pardons from King Henry VII and the Pope for the two murders he is known to have committed: the slaying of a priest who he discovered in an intimate embrace with his wife and the revenge killing of John Herthill, who had assassinated his father John Brome. If Nicholas had been forgiven for these acts, was there perhaps some other crime for which he felt he should do penance? Had his original memorial, a large marble slab with a brass of him in his armour, been removed because it was felt to be too good for him?

Researching the life of Nicholas Brome

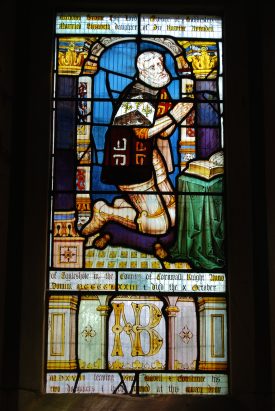

Few traces of Nicholas Brome remain in the manor house at Baddesley Clinton (now in the care of the National Trust). Even the stains on the floorboards in the library that were once believed to be the blood of the priest murdered by Nicholas have been found to date from a later period. It is St. Michael’s Church that provides more evidence and feeds the mystery. The church holds both Nicholas Brome’s ignominious grave and a wonderful East Window commissioned by his very righteous son-in-law, Sir Edward Ferrers. This window depicts Nicholas as a pious man of equal standing to Ferrers himself, and so further supports the idea that the world had forgiven him for his crimes.

The search for Nicholas Brome’s motive in insisting on a vertical burial took me to the two main archives in Warwickshire: Warwickshire County Record Office and the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust. Antiquarian records did indeed note the two murders but beyond these, I could find no suggestion of further crimes for which he might wish to punish himself. One interesting discovery was that Nicholas had been married three times: first to Elizabeth Arundel (whose marriage in 1473 is recorded in the East Window and who dallied with the priest), then to Katherine Lampeck (who received the freehold of Woodloes Manor together with her husband in 1506) and finally to Letitia Catesby (who is mentioned as his ‘present wife’ in a conveyance of 1511 and became his widow). Letitia (or Lettice) bore Nicholas Brome several children and so must have been very much younger than him. What prompted her to marry a known murderer so much older than herself and did she know the reason for his demand to be buried standing up?

Imaginative leap

It is hard to recreate the life of Nicholas Brome from the historical records. ‘The past lies as much in the realm of the imagination as does the future’1 and to adequately do justice to his intriguing story demands an imaginative leap. Discovering the existence of his third wife and widow, Lettice, provided me with a perspective from which to reflect on his life and make this leap. The result is a novel that puts forward a possible motive for his most unusual burial.

‘My Husband: the Extraordinary History of Nicholas Brome’ by Anne Elliott, published by Troubador, 2018: ISBN 9781789013122.

1 Attributed to Paul Zucker, German author and architect

Comments

Add a comment about this page