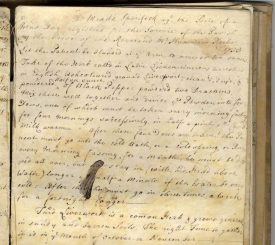

In 1735, the Revd George Hammond of Hampton Lucy ordered that a recipe against ‘the Bite of a Mad Dog’ be registered in the parish register ‘for the Service of the Parish’. Initially, you might think this is a rather odd thing to include in amongst the recordings of baptisms, marriages and burials for the parish. It is certainly the only known parish register held by Warwickshire County Record Office that contains such a recipe. However, it is not totally unique. Similar recipes can be found in the parish registers of Kingston Seymour and Axbridge (both in Somerset) and Weston Under Penyard and Bridstow (both in Herefordshire).1

Revd George Hammond

We can suppose that Revd George Hammond was a well-educated man. Born in 1693 in Gawsworth in Cheshire, he went up to Brasenose College in Oxford aged 16 and obtained his MA in 1720. His father (John Hammond) had married the sister of George Lucy of Charlecote, so as the Lucy family held the advowson of the parish of Hampton Lucy, it was only a matter of course that Revd Hammond should become the rector there.2

When Revd Hammond died in 1760, aged 66, he left a considerable amount of money for the benefit of the poor in his parishes in his will. So, Revd George Hammond had good connections, a good education, and as rector showed concern for his parishioners.3

The recipe

The recipe, which is described as ‘Dr Mead’s Specifick’ against ‘the Bite of a Mad Dog’, was published in August 1735 in The Gentleman’s Magazine, a monthly publication offering news and commentary on topics of the day (early contributors included Samuel Johnson). As it is a word for word transcription and matches the date given in the register, we can be fairly sure that this is where Revd Hammond found the recipe! The recipe itself is somewhat older, having been published in 1697 in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society as part of a letter from George Dampier to his brother William (a famous explorer).4

The recipe calls for the patient to ‘be blooded at ye Arm’ and then take the medicine which contained ‘the Herb call’d in Latin Lichen cinereus terrestris’ (best collected in October and November) and black pepper in warm milk.

The contemporary name for the condition (or more specifically, the main symptom) passed to humans through the bite of a mad or rabid dog was hydrophobia – an irrational fear of water. Mirroring this, Dr Mead’s treatment involved regular submersion in a cold bath, spring or river (with the caveat that should the water be very cold, the patient should not stay in ‘longer yn half a Minute’).

Types of recipe

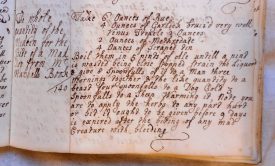

Dr Mead’s recipe was just one of several types of ‘mad dog’ recipes promulgated in print around that time. After the whole of Caythorpe parish in Lincolnshire were apparently bitten by mad dogs, the cure taken by the parishioners was kept at the parish church as ‘all that took this Medicine did Well, and the rest dyed Mad’.5

The Caythorpe recipe, which consisted of rue, garlic, treacle, methredate and scraped tin, was likewise widely shared, ending up in parish registers such as that of Axbridge as well as various account and recipe books of the time such as Mary Wise’s recipe book, also held by Warwickshire County Record Office.6

Other cures included the so-called ‘Tonquin cure’ which included more exotic ingredients such as cinnabar and musk (associated with Sir George Cobb, this was also printed in The Gentleman’s Magazine in March 1738) and the Ormskirk cure, which was sold commercially (again, the subject of a letter in The Gentleman’s Magazine in August 1753).7

Medical progression

Such cures gradually lost favour though the fear of bites from ‘mad dogs’ continued well into the 19th century. The ‘cure’ however by this time focused on the wound itself and the prescription of opiates until Louis Pasteur developed the vaccine for humans in 1885.8

So, to a great extend, Revd George Hammond’s belief in the need to record the recipe for his parish was typical of the era he lived in. Though sharing the recipe via the parish register was fairly unusual in Warwickshire, it was not unknown elsewhere and helps to demonstrate his concern for his parishioners.

This article is based on a Show and Tell talk given at Warwickshire County Record Office. The recipe was also Warwickshire County Record Office’s Document of the Month in September 2012. Further articles can be found on their website.

![Receipt [recipe] for the bite of a mad dog, C18th Receipt [recipe] for the bite of a mad dog, 18th century | Warwickshire County Record Office reference CR 2981/6/3/47](https://d23iiv8m8qvdxi.cloudfront.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/CR2981_6_3_47_mad_dog_compressed-275x439.jpg)

Comments

I have since discovered that Mary Wise’s recipe book also contains a transcription of Dr Mead’s ‘Receipt’ which is described as being ‘published in the Craftsman [another contemporary magazine] Augst 30 1735’. So, perhaps Rev. Hammond didn’t take the recipe from the Gentleman’s Magazine after all. At the least, it shows just how well circulated the recipe was that year!

Add a comment about this page