This document is one of a number of medical recipes preserved in the collection relating to the Willes family of Newbold Comyn. This bundle consists of documents written in various hands from across the 18th and 19th centuries, including handwritten prescriptions addressed to Edward Willes and printed advertisements for remedies. The documents contain cures for a range of ailments including epilepsy, asthma, miscarriage, the falling sickness, and dropsy. These remedies range from the benign (a cure for dropsy involving juice of the herb Pallitory of the Wall mixed with three pounds of clarified honey) to the repulsive (a cure for epilepsy in children involving a powder mixed with the innards of a mole, ‘caught in March, when they are the fullest of blood’).

‘This pain in my ear’

One piece is of particular interest, and documents the process of a woman, Lady Amherst, seeking treatment for her severe earache in 1813. It has been copied out at a later date by a person (perhaps Edward Willes?) who evidently had a keen interest in medicine, perhaps to use as a recipe for their own treatments. In this document we find evidence of a whole host of medical processes.

Lady Amherst writes to her daughter that the pain in her ear, which had lasted ‘many months’ was treated

‘with Leeches Blisters Cupping and Calomel Purges repeatedly, all of which… made it worse’.

She then went to one physician and his companion, who told her it was

‘an affection of the nerve… and thought electricity might do me good’.

She underwent this ‘several times’ and found ‘no benefit’. Finally, she was advised by a ‘surgeon of great eminence’ to try

‘a Plaister comprised of Half an Ounce of Cienta & a Quarter of an Ounce of Extract of Opium/Hemlock and Opium… well mixed together and spread upon some Apothecaries sticking Plaister of a size nearly of a Crown Piece & left on till it drops off…’

This appears to have been successful. She writes that

‘a quarter of an hour after I applied it I found relief & in an Hour I was well, but strange to tell that night when it fell off in my sleep the pain returned, on putting on the Plaister it again subsided’.

Modern medicine: electricity

This document is dated May 31st 1813, which is relatively early in the use of electrical therapy and is prior to its mainstream acceptance in academic medical circles. The use of electricity as treatment, particularly for psychiatric ailments, did not develop widespread usage until the second half of the 19th century.1

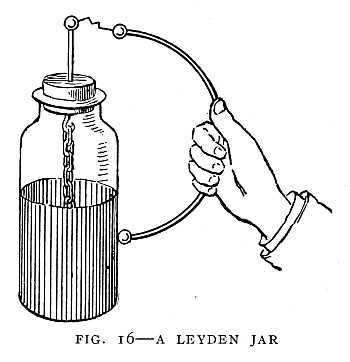

However, the study of electricity has always had a medical context, and even during its early days in the 18th century scientists were applying their inventions as cures for patients. For example, Benjamin Franklin developed a ‘Magic Square’ in c. 1750 to deliver an electric shock to patients, and in 1759 even the Methodist preacher John Wesley treated patients with electricity stored in a Leyden Jar.2 These treatments would have been very different from the process of Electroconvulsive Therapy that we may be more familiar with today, which involves the induction of seizure by application of electricity to the brain. These earlier applications would instead have involved brief electric shocks to other body parts such as the chest or side.

It is hard to say precisely what the procedure as experienced by Lady Amherst would have entailed. It is interesting to note that she does not elaborate further on the treatment; perhaps it was assumed that the intended reader would already have an understanding of the process?

Herbal remedies: opium and hemlock

Opiates have been employed as painkillers for many centuries and the active substance, morphine, is still used today. However, more surprising may be the use of hemlock for medicinal purposes, as we are most familiar with its highly poisonous nature. The plant was famously used to poison the philosopher Socrates, and physicians of the 19th century would have been aware of the risks and used the plant sparingly.3 In fact, the poisonous element of the plant, coniine, disrupts the nervous system causing a sedative effect or paralysis. This may be why the treatment was effective for Lady Amherst, alongside the effect of the opium. The ‘cienta’ which they were mixed with is another name for the plant knotgrass.

It would certainly be interesting to learn whether Lady Amherst continued the treatment, or whether it had a lasting beneficial effect. It does appear that this letter was written some time after the event, as she speaks of the earache being ‘long before I went to Ireland’, and the writer certainly appears convinced by the remedy.

While cases such as Lady Amherst’s may have been used to develop cures and techniques by physicians at the time, for modern readers they serve to emphasise the experimental, anecdotal, and above all personal nature of medicine as it developed in the 19th century.

1 A. Helmstädter, “The History of Electrotherapy of Pain –– or: What Voltaren has to do with Voltage” in Pharmazie 58 (2003), 151-153.

2 Alexander J. R. Macdonald, “A Brief Review of the History of Electrotherapy and its Union with Acupuncture” in Acupuncture in Medicine 11, No. 2 (Nov 1993), 67.

3 Ashley Mathisen, “Mineral Waters, Electricity, and Hemlock: Devising Therapeutics for Children in Eighteenth-Century Institutions” in Medical History 57, No. 1 (Jan 2013), 28–44.

This article is August’s Document of the Month for the Warwickshire County Record Office. Further articles can be found on their website.

Comments

Add a comment about this page